What’s Wrong With Purpose? How Do You Fix It?

By former CMO, UN World Food Programme, Saul Betmead

It seems everyday there is another debate about the importance of purpose in business, another discussion about the pros and cons of purpose-led marketing campaigns dominating at global awards. This is not a new conversation, and many fine minds have sought to unpack this whole area from different angles: There are questions of how we got here, the most intriguing of which is Tom Roach’s argument that ‘The dominance of brand purpose in marketing is perhaps the inevitable consequence of advertising people being told by everyone else, for about 150 years now, that they’re liars. That what they do is deceitful, that it’s of little or no positive value to society, that it doesn’t matter.’. There are many legitimate questions about whether it matters at all from the likes of Mark Ritson and his sparring partner Byron Sharp.

But for someone who has long found the idea of purpose as frustrating and confusing as it is inspiring and helpful, the most intriguing questions lie in why this is the case, in why when it works, it seems to really work, and why when it doesn’t, it can do so much damage. And therefore the bigger question to answer is how do you approach the idea of purpose to maximise the benefits and minimise the pitfalls?

What’s right with purpose

Purpose has become a dominant theme of the business world. This isn’t really a surprise, if by purpose you mean an organization has a clear sense of why it exists, what value it seeks to consistently deliver to its customers, its employees and stakeholders. Without this ‘Organizing principle’ as Contagious Founder Paul Kemp-Robertson calls it, it’s really hard for an organization to navigate key decisions about where it is going, how it is going to get there and how it will adapt as the world inevitably changes around it.

You only have to look to the likes of Nike and their ‘Bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete* in the world (and the most powerful bit…) *If you have a body you are an athlete’; or Disney’s ‘To create happiness through magical experiences’ – to understand why the really good ones both inspire and guide, help shape decisions, why they might make a big difference to a company’s trajectory.

It’s when you define an organization’s purpose as standing for something beyond its product and service, something that positively impacts people and planet, that you get the debate. The jury is still out, there are valid arguments for and against, so that right here, right now, it’s still more of a moral argument than an absolute commercial one – is this the right thing to do? Vs. Will this make us more successful?

I suspect it is only a matter of time before the expectations about certain company behaviours (regarding a responsibility to take care of the planet and its people), become disproportionately important in choosing one organization, its products and services over another. Only a matter of time before it becomes a dominant, potentially decisive driver in customer-client, talent-employer and client-partner relationships, alongside those of money, quality and time.

If you are building a purpose, ESG must be integral. The question, as we will unpack later, is at what level should that be?

There is another important reason why finding a company’s purpose remains important to so many: whether we like it or not, we are not rational decision makers, we are emotional ones. We understand the world through logic and facts but our decisions, big and small, are more often than not defined by how we feel about something. Often, we struggle to explain why we choose, we post rationalize, because how we feel about things is not that easy to fathom. It therefore makes a great deal of sense, when explaining your organisations focus to those who matter, inside and outside the company, that you are able to tap into something deeper, bigger than the actual product and service – so that people are buying something but also buying into something.

The more cynical amongst us will legitimately ask – ‘What happens if we are talking about something very functional like washing detergent? You seriously expect us to use that kind of language in the business of cleaning clothes?!’ You only have to look to Unilever’s now legendary reframing of its Persil/Omo business to see the value in this kind of ambition. From the efficacy of getting cleaner clothes to championing the vital importance of play for kids’ development, where dirt isn’t something to be hated, but is something to be embraced, where Dirt Is Good. They reframed the entire category in their image. Their products and services took on a very different role, they felt different. Did that remove the need for performance, the importance of price? Of course not. Might it have made the difference in a decision to choose them? Yes it could have. Did it make you want to work for, or stay with an organisation that wanted that for kids? Damn right it did.

The dark side of purpose

But it is here where things can go most wrong. Because it’s potentially so powerful as a driver of relevance, differentiation and engagement, the urge to find such a deeper role is incredibly strong. So strong in fact that you’ll see examples of smaller initiatives designed to make an organization, its products and services feel like they have a social purpose, but (even though they are made with the best intentions) end up feeling like tokenism, like purpose-washing, because the organization isn’t able to deliver on that promise more broadly, more deeply. Or it isn’t what they are about at all, leaving you thinking, ‘What did that have to do with that category?’ It’s not only confusing but also risks damaging that most precious of business assets: trust.

Re-thinking purpose through the lens of conviction

So how do you approach the idea of purpose to maximize the benefits and minimize the pitfalls?

It starts by understanding that, in the words of Mark Green, Accenture Songs Lead in Australia and New Zealand, ‘A great purpose drives galvanizing conviction for the whole organization’. In other words, a purpose is only as good as the organization’s depth of conviction to it.

If looked through the depth of conviction, the opportunities (deeper meaning, the glue that binds, guides and reinforces, a clear role in critical ESG agendas) and the challenges (tokenism, lack of clear connection to the actual business and category the organization is in) make more sense. The lens of conviction provides a frame to both diagnose the problem with purpose and find a solution.

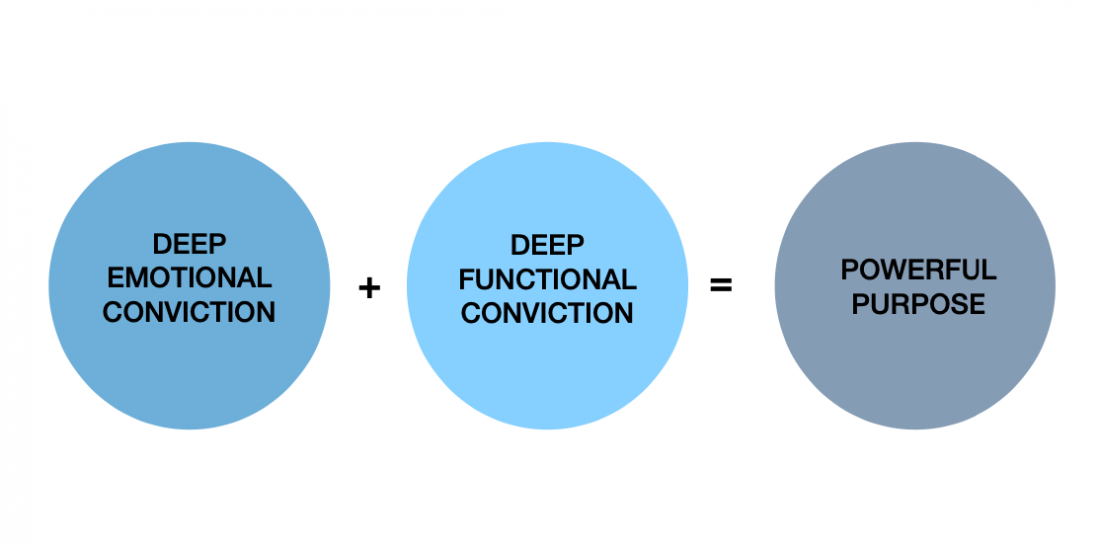

Purpose must create deep emotional conviction

What drives a deep sense of conviction to something? It’s how you feel about it. It answers questions: Does this move me? Does this motivate me? Does it drive my intuition about how to act?

These feelings are often born from finding something grounded in the category, the product or service, but about much more than it. It changes from ‘This is useful, this should be done’ to ‘I feel deep in my bones this is important, this must be done’.

It is this dimension that lights the fire, and then lights the way. It’s why you join, it’s why you stay, it’s why you are more likely to buy and keep buying. It drives loyalty beyond reason.

Purpose must have equally deep functional conviction

It is here, when we ask how is that conviction delivered, that purpose’s worth must be measured: how deep does it go?

Is it Marketing deep? Is it brand deep? Is it a specific product and service? Is it business deep? In what? In the how? If you look at those criticized for tokenism or purpose-washing, it is often not a lack of emotional conviction, but a lack of deeper functional conviction that is the problem. The purpose is marketing deep rather than brand and business deep.

This isn’t just a credibility and trust issue. This is a core business issue. If you look at Nike, the conviction that supports and drives its purpose is everywhere. Its purpose not only means innovating to create the best shoes and equipment, but one that drives services and coaching to unleash human potential, whoever they are, wherever they are. It also drives its marketing and comms, creating symbolic campaigns that consistently shape the category and the culture: ‘Find your greatness’ TV spot is both my favorite ad of all time, as well as the embodiment of ‘if you have a body, you are an athlete’, it leaves a lump in my throat every time I watch it, makes me believe I can do better.

When looked through this lens, you find a truth: the deeper the conviction, the better the purpose.

What is intriguing here is that many of the really powerful purposes, whose convictions are truly business deep, often don’t have an ESG agenda explicitly mentioned. They are defined, but elsewhere. What this means is that any attempt to create a system for delivering a powerful purpose, must allow for critical ESG challenges of our time to be addressed in two different places: as the core business focus, which works for someone like Patagonia and/or as a part of its principles of action, in how it delivers those products or services.

In defining what makes a great purpose, we therefore need an approach that can allow for this difference, to give permission for the purpose to have a different focus.

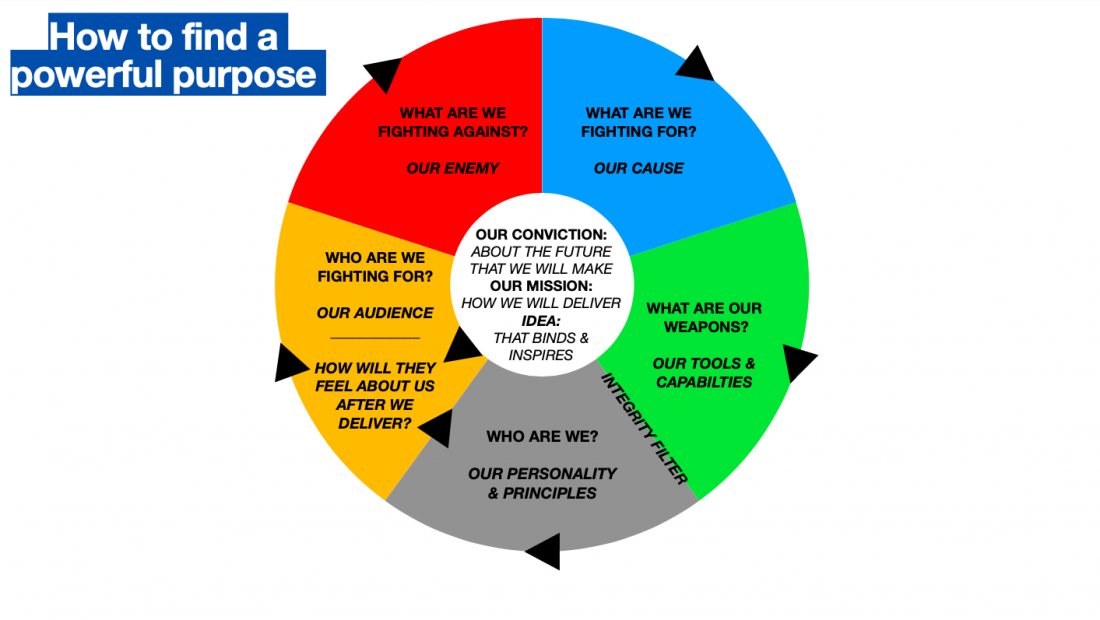

A simple system to find deeper conviction

So we now have a sense of what elements a great purpose must have, but how do you find and codify a deep conviction that underpins a great purpose?

It begins by changing the body language of how we think about it, how we talk about it. Shifting from talking about strategy, business model, growth, target audience need, competition, USPs, value propositions, resource and capabilities and their like, to one that is more human, emotional, steeped in metaphor and analogy:

Who are you fighting for? Who are they? What do they believe? What are their dreams, their fears?

What are you fighting against? What is the real enemy? What’s wrong with the status quo that needs fixing? What beliefs, what systems hold the status quo in place?

What are you fighting for? What is your cause? What are you championing? What does the world look like if you succeed to make the change?

What are your weapons? How exactly are you going to tackle this enemy, and champion this cause? How do these weapons work together? How are they symbiotic, how do they reinforce each other? Why are you different from others? Are you different enough for it to matter? What do you believe the future looks like and what will you do to shape it? (including predications about the evolution of the category and beyond, technology).

Who are you? Your personality. How do you turn up? What are you like? What impression will you leave? What things make you most like others? What things do you detest?

Who are you? Your principles. How do you do what you do? What are you willing to do? What will you not do? What are your red lines, especially in terms of ethics and environmental concerns? Think how you make things, how you treat the people involved in every aspect of the process and its management. If you can’t deliver without going against your principles, then either the weapons or the principles need to change: it’s an integrity filter.

How do you simplify all of this in the compelling way? – What conviction drives your purpose? What mission defines what you will do? What idea can hold it all together? So that when you read them… you just know.

How will those you are fighting for think and feel when you have done what needs to be done? So lastly, we close as we began, with those we serve: Is their life better? Do they feel how we wanted them to feel? If not, why not? The cycle begins anew, what more can we do? How can we be better?

If you think of it as a story that builds, this approach forces clarity, insists on integration, makes workable the aspiration, makes tangible the principles the business and brand holds true. One that is both inspirational and practical, visionary and grounded, whether you are a mature business or an aspiring start up.

A clear deep conviction that everyone can rally around is what makes a really powerful purpose.