Untapping The Potential Of Distinctive Brand Assets

This article has been co-authored by Sue Daun, Executive Creative Director at Interbrand London, Marcelo Ferrarini, Senior Consultant of Strategy and Analytics at Interbrand London and Molly Frampton, Junior Consultant at Interbrand London

If you work in the creative industry, you are probably very familiar with the works of Professor Byron Sharp. Agree or not, his bestselling book ‘How Brands Grow’ has transformed how we think about everyday brand management. His theories have popularised the notion that consumer purchase decisions are shaped by three factors: ease, mental and physical availability, and perhaps the most compelling, distinctive brand assets.

In its simplest form, Sharp’s argument is that distinctive brand assets are the key drivers of ease of recognition and purchase, whit little or no role for meaning or novelty. Is that all?

From a rational perspective it makes perfect sense. But if you consider the rapid transformation of the FMCG industry, suddenly the ‘scientific’ argument feels flawed. On average, 30,000[1] new products are launched every year, constantly widening the pool of consumer choice. Private label sales are experiencing exceptional global growth (at 16.7% between 2015-16[2]), partially as a result of the careful ‘borrowing’ of packaging cues from established brands. And, let’s not forget that consumers purchase channels have changed beyond recognition. Gone are the days where purchasing a toothpaste involved a trip to the local supermarket, followed by a 15 minute browse of the aisle. Online shopping or e-commerce is fast becoming the channel of choice, with projections indicating it will be the largest retail channel in the world by 2021[3].

What does this all mean? That consistently applying the same set of distinctive brand assets is not enough to influence purchase. As the category becomes more crowded, with new product launches and copy-cat private labels, what makes a product distinctive has to stretch far beyond it’s packaging elements. Why not, then, explore the possibility that symbolism, meaning (here used as the symbolism and associations evoked by different design objects) could help to make distinctive brand assets even more distinctive?

Meaning you say: Let’s start with an example. According to Sharp, it is the constant presence of the asset that makes it distinctive and memorable. Which means that, if you took a pair of Havaianas and applied the Swiss flag, over time it would become an established, Swiss flip flop brand. In the same vein, if you applied the Brazilian flag to a box of chocolates, you would create a global Brazilian chocolate brand. Except we know that this contradicts reality: chocolate is Swiss, and Havaianas are Brazilian. That is because there is meaning and depth to the Swiss and Brazilian flags, or in this case ‘assets’. To be fair to the Australian professor, he does often mention the importance of working with existing brand attributes. By extending this point to incorporate desired associations to our distinctive brand assets, we will probably have a better brief to our creative designers and potentially higher impact at shelf.

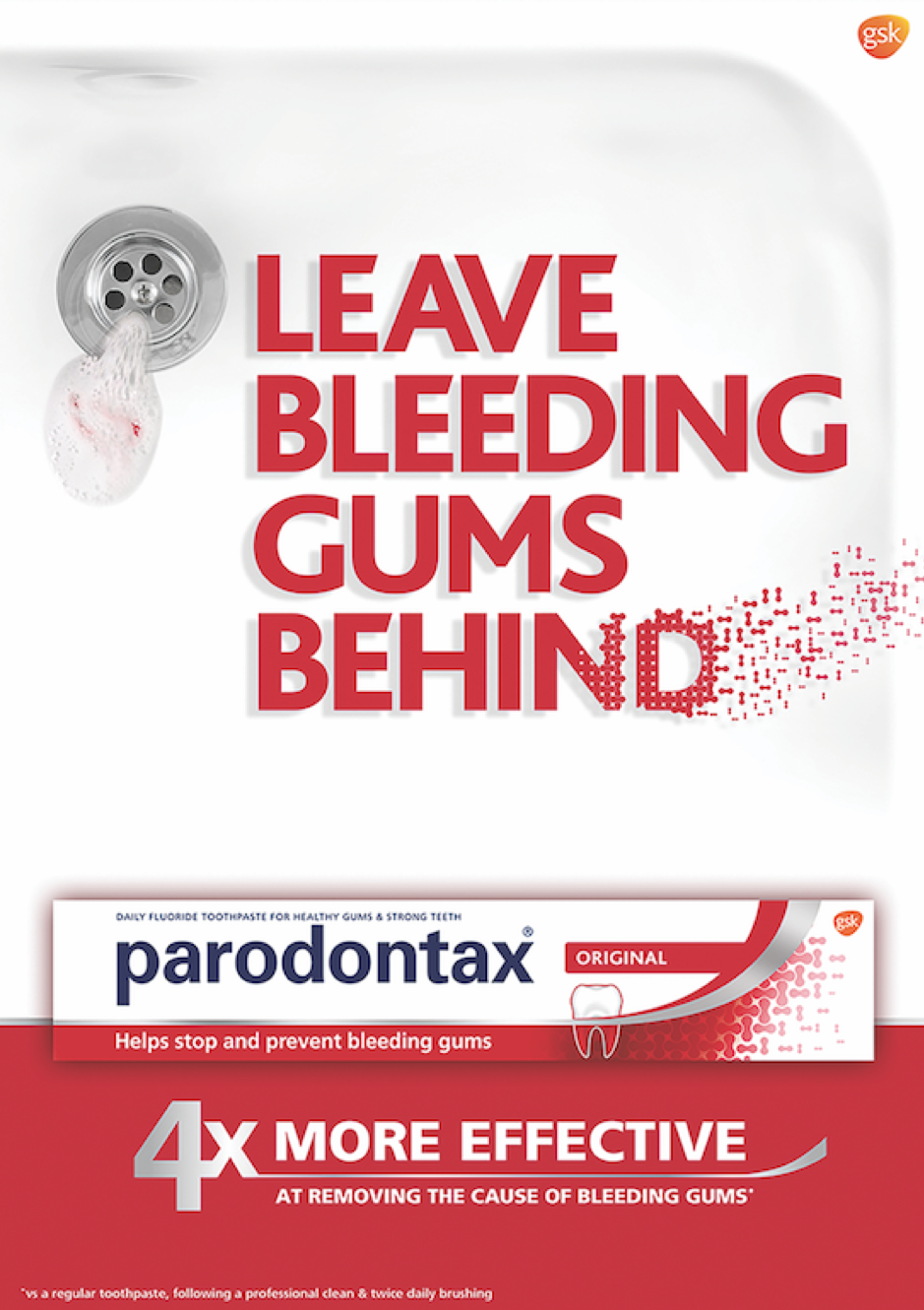

The rebranding of specialist oral care brand Parodontax is testament to the power of meaning. In a commoditised category where consumers often simply buy on autopilot, the shelf interaction needed to aid the recognition of a condition as well as stand out against competitor brands. Aside from the colour red and logotype, their brand assets lacked an authentic reason for being. They were failing to drive consumer attention and choice, who were not aware of the link between bleeding gums and gum disease – half of non-treaters see blood when they brush their teeth, but don’t believe it’s a problem. The other half know they have a problem but haven’t bothered doing anything about it.

This marked an open opportunity: to refresh the ‘distinctive brand assets’, to play a more educational role. Taking the existing red ‘asset’ and introducing a graphic illustration of platelets transformed it’s impact.

Consumers quickly associated the visual assets with parodontax, increasing memory recall and connecting the story told across different channels. A simple and elegant solution that befits parodontax’ premium price. [4]

Parodontax is now one of the fastest growing brands in the GSK portfolio, fuelled by the evolution of an existing asset.

(Communications produced in partnership with Grey Worldwide)

Having distinctive assets is one thing; applying them in a customer-centric way is another. Coca-Cola are amongst the world’s benchmarks when it comes to successfully harnessing the power of distinctive assets, globally identifiable from one glance of the aptly named ‘Coke red’[5]. And yet, the recent packaging redesign served as a valid lesson in the misuse of distinctive brand assets.

Taking the red to extremes and applying it across the whole portfolio left consumers at a loss. Which one is the full sugar? Are they no longer selling Diet coke? What happened to Coca Cola Life (that is another story). Whilst yes, it proudly championed the brand’s most distinctive asset, in the process it hampered how consumers navigate the entire product line-up.

Part of the reason behind Coca Cola’s ‘red’ confusion was the loss of other distinctive colours. Silver is as distinctive to Diet Coke as red is to the full sugar. Whilst we could argue that distinctive brand assets are solely for the purpose of recognition, the reality is that some do indeed serve multiple roles, such as portfolio navigation. Without those colours, consumers were suddenly at a loss perplexed by the seemingly endless sea of red on the shelf.

Finally, there is most definitely a lot to be said about the power of surprise. With the rate of technology and change at it’s greatest since, arguably, the beginning of time, the brands who are thriving are those who are agile, adaptive and most importantly, exciting. Dove are a brand synonymous with body confidence and female empowerment. From body washes, to foams, pro-age to baby Dove, Dove have continued to expand their offering to ensure resonance across a broad target audience. All the while, the presence of their most distinctive brand assets, the ‘Dove’ symbol and wordmark, is maintained. This allowance for flex means that Dove remain at the forefront of both consumer choice and recognition. In other words, by understanding the rules of distinctive brand assets, Dove have earned the licence to break them.

Byron Sharp’s theory behind distinctive assets are pushing the industry towards a more informed and effective brand strategy and execution. It has revolutionised how brands globally value their most iconic assets, and inspired a shift within the FMCG sector. The opportunity, however is to add to this approach the role of symbolism, associations, meaning and surprise to reinforce the distinctiveness of those assets. You could call it the perfect blend of science and art.