Modern Marketing Dilemmas: Is it still ok to talk about brand loyalty?

By: Mary Kyriakidi, Global Thought Leader, Kantar

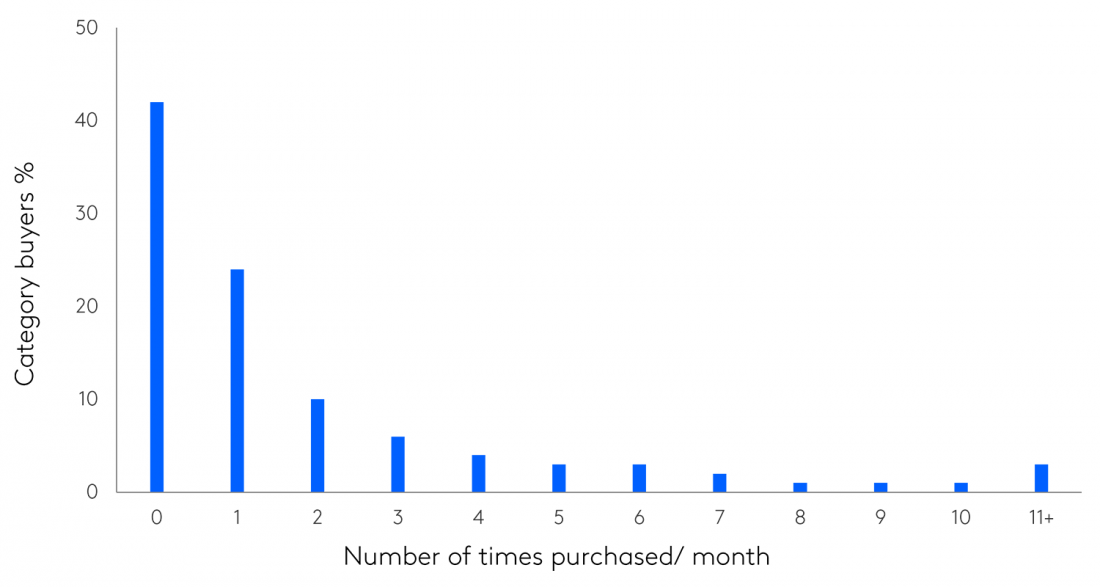

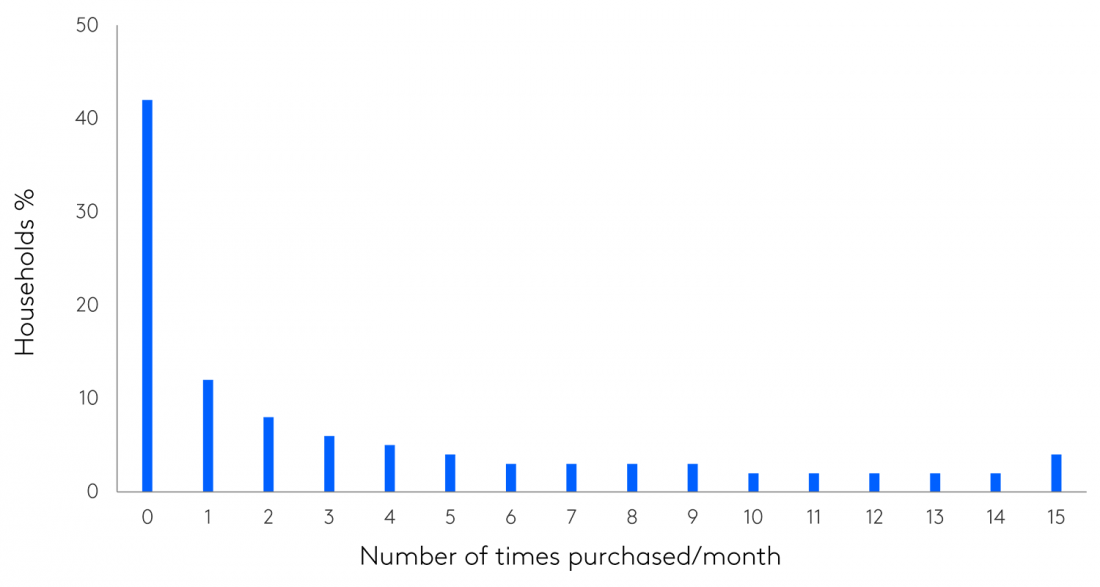

Kantar’s Worldpanel team then replicated the analysis at a category level. Let’s say there are budget limitations to pursue a sophisticated mass marketing approach, would it be better to focus on the heavy category buyers?

Using 2021-2022 UK data based on 200 FMCG categories, his findingswere not dissimilar to Steenkamp’s. As the data was laid out, that flipped hockey stick formed again although more faintly. Heavy buyers account for (on average) 60% of category spending (see below), so by solely focusing on them you would be ignoring 40% of the category sales. Similarly, by only targeting new or light buyers, you’d be dismissing 60% of the pie.

Average buyer frequency distribution across the top 200 FMCG categories

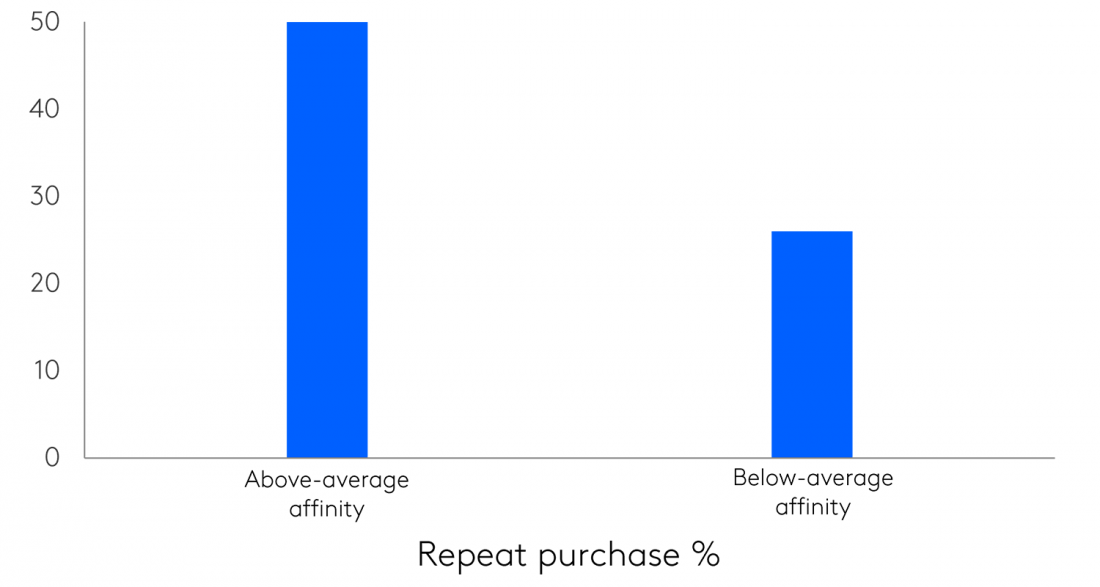

Study #3: Emotions can trigger repeat purchasing

As humans, we are creatures of habit. It’s mainly habit and social copying that drive our behaviour. But we can also develop strong emotions with ‘things’ that resonate with our needs, motives, values, and aspirations. Back in 2015, cross-divisional Kantar scientific minds joined forces and techniques to understand the relationship between brand equity and purchase behaviour and whether the former can predict changes in the latter. The team used shopper panellists’ purchase data and overlaid their attitudinal perspective i.e., how consumers perceived brands via a survey.

What did we find? Repeat purchase levels varied significantly between brand buyers with above and below-average affinity. Where affinity was high, the percentage of buyers who repeated their purchase in the following nine months doubled.

Percentage of buyers who repeat purchase in the following nine months

Given that the heavy buyers with a likely high brand affinity were not skewing our sample (we adjusted the results for pre-wave purchase frequency), we logically concluded that some brands are more effective than others in building affinity. Also, leveraging that affinity to drive purchase frequency is a sensible growth strategy.

Studies #4 & #5: Brand experience creates preference for all buyers

Daniel Kahneman has done extensive work into the brain and his discoveries around System 1 and System 2 thinking have had a powerful influence on marketing for over a decade. In his TED talk ‘The riddle of experience vs. memory’, he explains that “we don’t actually choose between experiences, we choose between memories of experiences.”

What does this mean for brands? Experiences turn into memories which form the various associations (both positive and negative) that consumers have for each brand. It’s what we call brand image – a step above salience. Yes, we might know that the brand exists, but what do we associate with it?

Two recent Kantar studies emphatically prove that experience plays a consequential role in getting a brand chosen, also that consumers are willing to pay a premium for experiences that will delight them. We surveyed more than 7k brands in almost 500 projects asking consumers to rank all touchpoints that impacted their memory (recall), but also the quality of their memory (whether it’s a good memory or not). The results? Product/ service experience posed as the #3 most influential touchpoint no matter the size of the brand or the age of the audience we looked at.

Experience is the #3 most influential touchpoint

Separately, we analysed the performance of more than 3,900 brands from our Kantar BrandZ global brand equity database (that covers 58 categories and 21 countries) in order to decipher what triggers people’s decisions. We discovered that experience influences repeat purchase and that brands that maximise retention yield a +7% growth. Because a good experience entices repeat sales.

‘Skimpflafion’ is a relatively ugly word reflecting what some brands have resorted to as an antidote to inflation/recession. “It’s like customer service…on diet” as Shep Hyken puts it. According to Forrester, a respectable 19% of brands skimped on the quality of their products or services in 2022. But it hasn’t gone unnoticed by the consumers: 66% experienced skimpflation and 87% of them vow to spend less or stop spending money altogether at brands that reduce service. Experience matters. So do brand associations. Without these, price becomes the single determinant of consumer choice.

Forget about loyalty, it’s all a matter of preference

At a very high level, the concept of loyalty promises strong feelings of support or allegiance, but in marketing, it’s become a very muddled idea. EBI’s marketing law of double jeopardy (a rule that states a brand with lower market share also has lower loyalty than its bigger rivals) crowned customer acquisition the only viable growth strategy and settled the acquisition vs. retention debate of over two decades. But in our view, it was a misplaced dilemma all along. The question to ask is not whether to target heavy or light/ no buyers, but rather: ‘how can I make my brand the preferred choice among all category buyers?’ This is what surfaces from our five studies; loyalty in marketing is nothing more than ‘the preferred brand’.

We see that both cohorts of current and future buyers have a fair impact on sales, also that people don’t buy randomly; their predisposition towards a product or service massively affects a brand’s chances of being chosen. The right response for marketers is to invest in building brand associations and expectations across the broadest audience, then to optimise activation to make their brand the easy and obvious choice.

Just remember: it’s not an either/ or. By increasing brand predisposition, repeat purchasing will go up too. And so will penetration – its growth pace will be determined by your activation spend and effectiveness.

Read more in the Modern Marketing Dilemma’s series below and get in touch to discuss how to increase preference for your brand.

This article has originally been published on Kantar